Ishtiyaq Shukri is the award-winning author of The Silent Minaret, I See You, and An Unwritten Life. The Silent Minaret was the first novel to win the EU Literary Award in 2005. He was born in Johannesburg in 1968. He lives in London, where he works in suicide prevention. (Author photo by AJAB.)

The coolie on whom the sun never sets

My heritage map, August 2024

Essay | DNA | On being a Muslim Jew

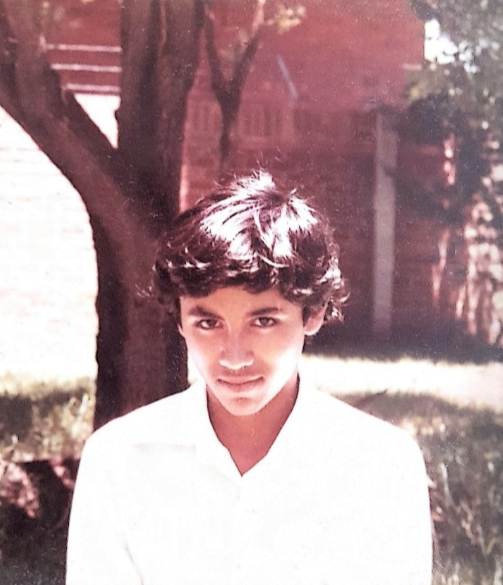

The most haunting photograph of my childhood, St Cyprian’s Cathedral, Kimberley, 1981.

About the child

When I had to decide on an image to accompany my essay, The longest shadow, published by Africa Is a Country in 2021, the most apt one was this photograph of me from forty years before, outside one of the many Anglican sites where I was sexually abused as a child: St Cyprian’s Cathedral, Kimberley, South Africa. It was taken outside and to the left of the Dean’s Door, near the statue of Sister Henrietta Stockdale, in 1981, the year I turned thirteen, and entered my third year of being abused. I felt the photo fitting because of its location, but also because of its subject, a child who was being sexually abused by two priests in the cathedral at the time. I wrote that 2021 essay under the close supervision of my therapist, who was guiding me towards identifying with the boy in the picture, rather than cutting him out, as I had been doing for more than forty years. It was a long and painful process. I wrote to my editor, explaining my selection: “this image has come to signify a lot to me in recent months. I’d like him to live in this new world we’re creating.” That new world remains a work in progress, and there is still a lot of work to be done. Since 2021, there have been many further disturbing revelations of child sex abuse and torture in the Anglican Church of Southern Africa and the Church of England. There will be more. To date, the ramifications have been disastrous. They will become more so. The future of the Church hangs in the balance, institutional corruption, complacency, privilege, dishonesty, indifference, “inherent arrogance” and entitlement amongst the root causes. The institution’s undoing and demise will be outcomes of its own making.

Towards creating a new and safer world for survivors of child sex abuse, this photograph appears prominently on this site because when adult survivors of child sex abuse speak about their experiences, that is exactly what society sees: adults. Our childhood trauma, as experienced by the children we were, is eclipsed, filtered and inadvertently diminished by our adult appearances. In instances where survivors have also achieved career success, public recognition, celebrity, and fame, many feel unworthy of their accomplishments, or fall further victim to their attainments through comments that diminish their trauma, like: It couldn’t have been that bad. You did quite well. What are your complaining about? All of this deflects attention from the heart of their story: the child they were. Consequently, their stories and struggles are judged by the public image they have learned to project as adults, rather than the actual abuse and trauma they experienced as children.

In many complex ways, survivors in denial unwittingly remain emotionally trapped as the children they were at the time the trauma intervened to derail their natural progression. Undiagnosed and untreated, the impact of trauma on child development is enduring and catastrophic. My psychiatrist described it as tampering with an aircraft’s instrument panel, resulting in the plane deviating from its scheduled flight path. Unguided, such an aircraft will end up in the wrong destination, or it could crash, or be shot down, or simply disappear from the radar without trace. The metaphors are chilling, the reality more so. One of the greatest tragedies of childhood trauma is that we will never know the adult the child would otherwise have become. In this regard, my psychiatrist went even further, describing child sex abuse as akin to double homicide: the child and the adult they would otherwise have been. This explains the profound sense of loss many survivors carry. Simply put, it feels like mourning the death of a child, the child they were.

That is why this photo features prominently here today. Since it was first published in 2019, it has become one of the images most associated with me. No longer ashamed and silenced, dead and relegated, this boy has not been forgotten. With a lot of psychiatric support, counselling, research, study, and professional training and development, I remember him. I am speaking up for him now, in a way he could not speak up for himself then. I am standing up for him now, in a way not one of the adults in his life stood up for him then. That was their single most important task. They failed miserably. Years of work have led me to acknowledge the link between the acclaimed 2015 film, Spotlight, and my own experience: If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to abuse one. People knew. It is in defence of this boy that I am now being the adult he should have had then. It is in his defence that I am taking the Anglican Church of Southern Africa and others to court in South Africa for child sex abuse. Legal proceedings in the Western Cape High Court, Cape Town, are imminent.

Although I used to avoid looking too hard at it, this photograph was always prominently displayed at home. On the surface, it is a simple picture, but zoom out, and the bigger picture is far more complex. I am not the only child in the original photo, which has been cropped in this published version. While I am relieved that I received the abuse, not them, still the question arises: Why me? With the strength and ability to study the photo more carefully now, I recognise the early years of my faraway look, the vacant absence of the daydreamer, which so many of my teachers commented on, and sometimes punished me for. While it seems like staring, it is in fact more like disappearing. It comes with not looking at, but through, beyond, and into oblivion. Not much understood at the time, today I recognise it as a sign of dissociation, a common involuntary coping mechanism in response to stress and trauma. I now understand my faraway look in this photo when I consider what I am dissociating from, looking not at, but through, through the lens, through the camera, through the photographer, who was in fact one of my abusers, the Anglican priest, Keith Thomas, sent to South Africa by USPG, the Anglican mission agency with links to slavery. Given my experiences of Thomas, I find this blog by Colin Amos, his former curate in Aberdare, Wales, now vicar of St Augustine’s, Kilburn, London, disturbing. It typifies the indifference and entitlement I reference above. Amos knows me well from my visits to Thomas in Aberdare between 1993-1996, and is aware of my abuse. Still, his blog stands, unrevised. Nevertheless, having avoided Thomas’s photo of me for more than four decades, I can now date, stamp, locate it, and put it in its place, all important steps on the path to recovery. That is why I can now describe it unequivocally as the most haunting photograph of my childhood.

Thomas took a lot of photographs of me, mostly by myself, but sometimes with others. Looking at this particular image now, I am able to ask: What is the paedophile priest observing? What is the paedophile recording? I am also aware of the public context of this image, outside the cathedral, after Sunday Mass. I now also remember that there were onlookers to the scene. What goes through a paedophile’s mind when they set the scene for such a public photo? Why were two paedophile priests, Keith Thomas and Roy Snyman, allowed to operate at the same time in the cathedral church of one of the largest diocese in South Africa, the Diocese of Kimberley and Kuruman? How does this fit into the broader context of the Church in Africa? Resulting from empire, the Anglican Church is one of the largest Christian denominations in the world, and Africa is where most of the world’s Anglicans live. In addition to South Africa, there have also been reports of sex abuse in the Church across the continent, in countries like Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Namibia, Zimbabwe and Zambia. I am now able to slot this small image of me into that bigger Pan-African picture of abuse, and recognise this photograph unflinchingly for what it is: not just of a child, but also of a crime scene—my body.

These are amongst the issues that haunt adult survivors of childhood trauma and abuse, and their recourse is often to blame themselves. In fact, self-blame on the part of survivors indicates a “good” perpetrator at work. My predators were excellent. I blamed myself and felt complicit for decades, until Desmond Tutu made his hypocritical comments about Oxfam on 15 February, 2018. This is an example of the arrogance I referenced earlier, which is strikingly evident in the Church from Cape Town to Canterbury. I don’t believe that Tutu or the Church expected to be challenged; they simply occupied the moral high ground, their hubris making them blind to what would happen next, the revelation of child sex abuse inside their own organisation. On 9 March, Tutu claimed to be “mortified” by the revelations, and on 13 March, his successor, Thabo Makgoba “begged for forgiveness.” Televised statements by Makgoba about the abuse followed on 22 March and in his Easter Sermon on 1 April, the day I turned fifty.

These were excruciating weeks for everybody who was directly affected. For me, everything changed. I was in India, from where I was in close private communication with the Church. Upon my return to South Africa a few weeks later, I was admitted to a psychiatric facility in Pretoria on 15 April, from where discussions with the Church continued. Those discussions collapsed the following year, after I lost faith in the Church’s sincerity, and initiated legal proceedings in October 2019. Since then, the Church has been stalling legal proceedings with bureaucracy. Six years later, on 4 February 2025, Makgoba was again in the hot seat, yet again having to apologise for “exposing congregants to risk of sexual abuse.” How does such repeated behaviour of negligence and disregard by the most senior figures in the Church bear witness to the core values of the catechism, the Eucharist, and the sacraments of confession and reconciliation for what they have done, and for what they have failed to do?

When I look at the boy in this photograph today, I experience the action almost entirely as inverted: he is looking at me. This reminds me of the scene from the 1982 film, The Wall, in which Pink the boy wanders into an abandoned psychiatric facility where he finds himself as an insane adult, Pink the man, huddled alone in a corner. While Pink the boy runs away, the boy in this photo just keeps staring back unflinchingly, and it’s almost as though I can hear him asking me: What are you going to do? While the Church is good at making public statements of contrition—it certainly has had a lot of practice—it is also good at wielding private retribution on survivors who pose a challenge. In my experience, despite its public statements, the Church is not a survivor-focused organisation; I have written evidence to the contrary. The Church has not learned, and neither has it changed. The reasons are simple: it deems both to be beneath its stature, perceiving them as challenges to its authority. Instead, the Church remains under the illusion that it is exempt, that it presides in a sphere beyond the secular realm, and that honorific titles, purple robes and vaulted ceilings protect it from public accountability and prosecution. That is set to change. I am not in awe. I will not be deflected.

Child sexual abuse by priests is not only the abuse of the body and the death of childhood, it is also a violation of faith. In my experience, by stating that one has been abused by Anglican priests, one is not only taking on priests, but also the whole of the established imperial religious order, which, in the case of the Church of England, is inextricably intertwined with one’s acquired sense of Heaven and God, who one comes to imagine as a High Church Anglican dwelling between Canterbury Cathedral and Westminster Abbey. Pursuing these issues to the fullest extent is the work at hand. The ultimate driver behind my court action against the Anglican Church of Southern Africa and others: to speak openly and from an informed basis, as I am able to do now, in the most elevated and public arena of them all, not a sectarian place of worship, but a superior court of law. There, in defence of the child in this photograph, and to hold the perpetrators and their institution to account, I intend to go on the record and shatter the silence about child sex abuse in the Anglican Church of Southern Africa in the most public way at my disposal as an enfranchised citizen of a parliamentary democracy like the Republic of South Africa. The Church may hope it is, but throwing a dead abuser under the bus is not the end of the story. Survivors don’t want empty apologies from dubious men, we want justice, institutional accountability, and legal precedents. That, ultimately, is how you affect real change.

Ishtiyaq Shukri

London

28 February 2025

Related timeline: Help and resources: South Africa United Kingdom