My Imploding Worlds

From the riots in Pretoria to Brexit and the European “migrant crisis”, Ishtiyaq Shukri hangs his head in shame.

Like many people the world over, I live between countries, and as time has passed, I have developed an affinity with all of them. When I am physically present in one, the others are always in my mind. This is not always easy, but it has always been enriching. Only one thing could be more so—to be as physically present in all my countries at the same time, as I am mentally. South Africa and the UK are two of my countries, and while I am currently prevented from traveling to the latter physically, life is not only lived and experienced through the body, but also in the mind. Despite my physical exclusion from the UK, I spend a lot of mental time there, particularly in London. For so long I have lived in my countries simultaneously, it feels as though they have begun to merge—no longer separate places on the map, but one place in my head. In all, I see rampant racism, extreme wealth, abject poverty, disregard for human life, and utter contempt for humanity.

This has been a particularly difficult week for South Africa and the UK; and especially difficult for me because I am not physically present in either. Bad news always feels worse when one is far away. In Pretoria, the worst riots since the end of apartheid erupted over the nomination of Thoko Didiza as the ANC’s mayoral candidate in local elections scheduled for August. To see one’s capital city in flames is never easy, but in the case of Pretoria, it is particularly cutting to see images of the city on fire coinciding with the 40th anniversary of the Soweto Uprising of 16 June, 1976. The pictures of Pretoria in flames paint a thousand words, including the following eight: All is not well. Something needs to change.

News from the UK is equally vexing. On 16 June, I was driving in heavy traffic, the radio on in the background, when five words filtered through the din of the highway to punch me in the ear—British member of parliament shot. In the immediacy of the moment, the announcement competing for my attention with the lorry ahead, the thought crossed my mind that perhaps the shooting had occurred in Afghanistan or Iraq. Isn’t that where such things happen? I slowed down and turned up the volume to hear the details: not Afghanistan or Iraq, but West Yorkshire, England. I remember looking at the radio and asking out loud, “What?” Allow me to reach for the words from the protest song by the British rock band, Queen:

Is this the world we created?

We made it on our own

Is this the world we devastated, right to the bone?

If there’s a God in the sky looking down

What can he think of what we’ve done

To the world that He created?

Those lyrics capture some of the despair I have felt while watching my worlds imploding. That they grow ever more relevant, ever more poignant with the passing of the years, is an indictment, and I for one hang my head in shame.

We have reached a stage in human history where we have come to think of ourselves as advanced, viewing our age as the pinnacle of human evolution. Yet, I look around the world, particularly at the countries in which I have lived my life, and I cannot help but feel differently about the state of things. We use terms like the “developed world,” the “first world,” the “industrialised world,” to categorise, to elevate, or to denigrate, whereas I have a growing sense that only one category is increasingly relevant to ever-expanding swathes of our planet—the devastated world—because that is how most people on Earth experience life.

What meaning is there to any of our categories when the economic and foreign policies of rich countries in the ‘developed world’ are directly responsible for the poverty and insecurity of poor countries in the “developing world,” especially when those policies actively work against development, but foster destruction and annihilation instead. Let me give just one example, another of my countries—Yemen—pulverized by Saudi Arabia with British and American weapons.

And the dynamics of the fake categories we impose on the world are reflected in the horrendous language we use to talk about people. There are two current affairs items, which—along with Tony Blair—I have taken to muting. The first is news involving the American billionaire currently a front-runner for the Republican Party in the campaign for the US Presidency, and whose name I refuse to write. He has already had more media coverage than a bigoted idiot should. The other is the debate around Britain’s proposed exit from the European Union to be decided in a referendum on 23 June. I could no longer endure the vitriolic racism of the “Brexit” campaign, and so simply tuned out.

Similarly, if anything belies the myth of change in South Africa, it is the language South Africans continue to use, and the ways of thinking we continue to employ. Young privileged South Africans frequently argue that they are not responsible for apartheid and its aftermath as they were born after it (supposedly) ended. This kind of thinking is born out of that of their parents, who similarly absolve themselves of responsibility through claims that they did not know, or that they were merely abiding by the laws of the land, or that they were simply following orders. These falsehoods continue to be rampant in South Africa, where they are employed by the privileged to reconcile themselves with the continued states of favour they enjoy, and to absolve themselves of responsibility for the enduring trauma prevailing in the country.

And even as they employ these arguments, it is without any awareness of the converse being true—that if wealthy South Africans born after 1994 are not responsible for the state of the nation and therefore at liberty to enjoy their wealth, then poor South Africans born at the same time are not responsible for their poverty and therefore at liberty to protest. The truth is this: around the world, but especially in South Africa, privilege and poverty are inherited, and like most inheritances, you get them from your parents. Twenty-two years after 1994, who in South Africa still lives in townships? And how many township inhabitants are white? By what perverted thinking have white South Africans become victims? Of Africa’s ten richest people, three are South African. All three of them are white (men). This is the same perverse way of thinking that allows Israel to paint itself the victim of Palestinian aggression even while it has nuclear weapons and the world’s largest military personnel per capita.

Such flawed thinking allows us to hold on to, perpetuate, and justify racist stereotypes and attitudes. Take corruption for instance, often depicted as endemically African, whereas the facts tell another truth. According to Transparency International, the UK is in fact on of the most corrupt countries in the world, and London the world’s “number-one home for the fruits of corruption”. But who cares about facts when they conflict with our notions of the developed world, of the west, of the first world, and of Europe, which brings us to another revealing fact, which tells an altogether different truth: Europe is in meltdown because of its supposed “migrant crisis”, whereas in fact most of the world’s refugees live in poorer countries.

The same language used by privileged South Africans has been on abundant display in Europe. European countries have colonized the world, yet they descend into crisis when a fraction the world’s most desperate and vulnerable people arrive at their borders, not as colonisers, but as refugees. When the EU started sending refugees back to war zones created by some of its own member states, I felt nothing but shame. In 2004, I was awarded the inaugural EU Literary Award. Today, it is an award that leaves me with a deep feeling of betrayal and embarrassment.

In Britain, hysteria around migration has led to the prospect of a British withdrawal from the EU. Following the murder of Jo Cox, MP, there is now a petition sweeping across the UK to cancel the referendum on Thursday. I hope it will be called off, but that is unlikely. This referendum should never have been called for in the first place. If Britain wants to have a referendum, let it have one poverty and exclusion, particularly white poverty and exclusion, because in Britain, white poverty is invisible. And when it does appear on the national stage, it is as the butt of the joke in sitcoms from Only Fools and Horses to Little Britain. This referendum takes the world backwards, not forwards. It is a deceptive, indulgent, and shortsighted campaign, set upon tearing up Europe and dismantling the world. Is Britain so different, so exceptional, that it cannot be part of the European family of nations? This parochial agenda has serious international consequences because a British exit from the EU will leave Europe weaker, and let us not underestimate the global dangers posed by a weakened Europe should it all unravel.

On 28 June 1914, a Slavic nationalist Gavrilo Princip fired a shot that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg. The shot was fired in Sarajevo, but it travelled through Europe and around the world, igniting the World War I. Should Thursday’s referendum go ahead, I hope British voters will consider their choice carefully. I hope they will find it within themselves to look beyond their immediate horizons and consider the world as it is, a tinderbox, fragile, volatile, and highly militarized. This referendum campaign has revealed deep and wide schisms in British society, and British voters must consider who will be weakened, and who will be emboldened should the Leave camp win. The neo-Nazi nationalist movement, National Action has already voiced support for the killing of Jo Cox. I hope they will remember just how far and wide the bullets of European nationalists like Gavrilo Princip and Thomas Mair can travel and ricochet.

Let wealthy and powerful South Africans continue to delude themselves and to dismiss the grievances of the township. The level and spread of the violence in Pretoria may have been sparked by the announcement of a mayoral candidate, but it is fueled by deeper unresolved issues that go back decades, even centuries. There hasn’t been a reckoning in South Africa, and if you think 27 April 1994 was it, then you’re mistaken. The good will offered on that day has been spent. A new generation has grown up who care nothing for amnesties, or negotiated settlements, or rainbow nations. 27 April may have been your day of freedom, but it isn’t theirs. And why should it be when they don’t live in a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow, but in a township behind a hill? There hasn’t been a day of reckoning in South Africa, but if things don’t change tangibly and soon, there will be. And when it comes, it will be horrific, but it will not be without cause. No doubt, the pictures from that day will also paint a thousand words, including the following three: Lord help us.

Originally published by Sunday Times, Books Live.

Related:

Postapartheid South Africa’s negative moment

Marikana and the end of South African exceptionalism

Wits #FeesMustFall: Ishtiyaq Shukri calls on Wits University to terminate contract with private security firms

Dear Professor Adam Habib and Members of the Senior Executive Team of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg

I have in recent months been increasingly alarmed by the growing levels of militarized violence deployed against students from the #FeesMustFall movement at the University of the Witwatersrand by private security firms paid for by the University. I despair at the failure of imagination demonstrated on the part of the University in its inability to find and employ amicable forms of management and conflict resolution, and its readiness to resort to the old South African recipe of force to settle disputes instead. I am deeply concerned by the model the University has presented to the country: that in South Africa violence and force are commodities for sale to be purchased, at undisclosed amounts, even by a university. Purchased by senior executives—not of a corporation, but of a university—executives against whom such force is unlikely ever to be deployed. Private force, purchased by a wealthy institution to be aimed at its poorest students. And I am especially disturbed by the recent shooting of Fr Graham Pugin of the Holy Trinity Catholic Church next to the University. While I have wrestled with writing to you before, following his shooting, I can no longer remain silent now.

I’ll just state it plainly. South Africa is under occupation by private military and security firms now in possession of a combined arsenal of privatised force, which already outnumbers that of the state by five to one. And while they have the capacity to deploy levels of violence and force that surpass those of the state, they are not accountable to its citizens or to the state. In a democracy such as ours, state forces are rightly accountable to the citizens, and in the case of the shooting of Fr Graham, the Deputy National Police Commissioner, Gary Kruser has apologised unconditionally and set up an official investigation to be headed by the Gauteng provincial commissioner. Commissioner Kruser is not doing us a favour. In a democracy, he is holding himself accountable, just as he should. By contrast, unregulated private military and security firms are only accountable to their shareholders, shareholders for whom the use of force translates into the escalation of profit; profit to which you have contributed untold amounts. The threats posed by private military and security firms have been a long-standing concern of mine and are a central to my novel from 2014, I See You. One of the novel’s main characters, Leila Mashal outlines the threats in a key scene. I mention this to you only because that scene takes place in the Great Hall at Wits.

Having imagined the threat of privatised force in my fiction, I have found it very difficult to watch the violence unfold at Wits in reality, of which the shooting of Fr Graham is a startling escalation. Is nothing sacred anymore? When I set that fictional scene at Wits, the last place I imagined would one day become the setting for the greatest public manifestation to date of the occupation of South Africa by privatised forces was a university, indeed Wits University itself. This vexes me, because it is not easy to see the boundaries between fiction and reality implode at Wits, and because to me their collapse signals that the occupation has penetrated even our most respected centres of higher learning. You have stated that you have on a previous occasion reviewed footage of claims by students regarding brutality and abuse by private security agencies at Wits. You claimed to have found nothing to support those allegations. Maybe. But today I ask you to review the footage of images of brutalised priests and students now emanating from Wits. Are they evidence enough? Do you see what we see? What the rest of the world can see—even the Pope in Rome? Whatever these private security forces may have protected, it wasn’t the reputation of the University and it certainly wasn’t Fr Graham.

In January 2016, Concerned Wits Faculty and Staff wrote to you requesting the University to terminate its contract with these private security firms. Writing on behalf of the Senior Executive Team, you rejected their request.

Following the shooting of Fr Graham, I call on the Senior Executive Team of the University of the Witwatersrand to demonstrate conciliatory leadership. I call on you to consider the lives of the students entrusted to your care, if not on a contractual basis, then at the very least on an ethical one. I call on you to reconsider your decision, and for the University to terminate its contract with these unaccountable private security firms. In the face of their insidious occupation, which is now at least no longer invisible, is it not also the responsibility of a university of good repute to be discerning about the threats they pose, to demonstrate dissent by also shedding light on how they undermine our democratic procedures, and to take the lead in standing up to defend those procedures rather than participate in their erosion through silent financial transactions with secret unaccountable forces? And if these are not also the responsibilities of a university, then to whom do we entrust them when we are under occupation?

Sincerely

Ishtiyaq Shukri

11 October 2016

Originally published by Sunday Times, Books Live.

Related:

A decade later, #FeesMustFall remains a watershed moment in SA’s history

The Muslim Jew: From Mexico in the west to the Solomon Islands in the east, I am truly the coolie on whom the sun never sets

In January 2024, I received a serious medical diagnosis. I decided it was finally time to take a DNA test to answer long-standing questions about my ancestry before it is too late. The results were astounding, radically altering received ideas about who I am, and the country I was born in.

Since embarking on my grand voyage, I have become increasingly weary of the question: Where are you from? In South Africa, I’m rarely asked it. If ever, nobody disputes my answer; although considerable room for inclusion remains, at least we know that diversity is amongst the most defining features of our country. However, outside South Africa, my answer is often contested. You don’t look South African. You don’t sound South African. Then the probing begins. Where were your parents born? South Africa. And your grandparents? South Africa. What about your great-grandparents? Seriously? On one occasion, a policeman in Cairo refused to believe me, insisting I must be Egyptian. That we spoke in Arabic did not help dissuade him, so he demanded to see my passport. When I said that it was in my apartment, he threatened to arrest me.

Over the decades, all this delving has become exasperating. They are asking once, but I get quizzed endlessly, so that I am constantly having to narrate my begats like the Book of Genesis on repeat. To spare myself, I vary my responses. For a quick resolution, I might say: India. At other times, I might pose a question—Where do you think I’m from?—resolving to accept whatever they guess. I knew it! There’s something about the face/hair/complexion, they say, satisfied that they know me better than I know myself, even when, as happened on one occasion, they had guessed: Japan.

More recently, I have simply come to answer: North London. One of the most diverse cities in the world—just 36.8% of London’s population is White British—I have ample room to blend in, wearing the city like a coat of many colours. However, even in this highly multicultural context, my response still raises questions, illuminating how different demographics in the UK respond to the topic of origins. Global Majority British people are generally accepting. Only newcomers, random tourists, and less cosmopolitan white British people not from London continue to ask: But where are you originally from? This is a disheartening question to be asked repeatedly; it is not inclusive, it disregards one’s preferred response, it prioritises the questioner’s curiosity, it favours their narrow view of people and of the world, it overlooks complex historic and contemporary realities, it is blind to individual experiences of displacement and belonging, all of which leads to feelings of alienation and exclusion, a reminder that one is never going to be allowed a full sense of belonging, but instead be doomed to feeling eternally out of place. Therefore, I have stopped collaborating with the inquisition. North London is my present. I draw boundaries around further disclosure, only providing details in safe spaces, and as I see fit.

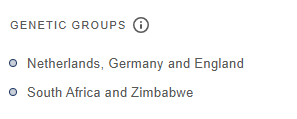

While my DNA has revealed that I am of English, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh descent, meaning I am descended from all the four countries that constitute the United Kingdom, I would only go so far as to call myself a Londoner. Despite whatever regressive immigration policies are being peddled by the British government of the day, London itself stands in sharp contrast to them. It is a truly global city, the full extent of its pluralism increasingly manifesting the more time one spends in it. With more than 300 languages, its linguistic diversity alone surpasses that of any other city. I am continually awestruck by the people and stories I encounter in such a huge melting pot. Founded as Londinium by the Romans in 47 CE, London accommodates extraordinary levels of complexity, as it has done for almost 2,000 years. This is why I call it home, and why, in recent years, I have become increasingly selective about venturing outside the M25, the orbital motorway encircling the capital; attitudes towards diversity beyond are not always as embracing as within.

In recent years, marked by escalating Tory atrocities, I have become progressively guarded about discussing my nationality. Everywhere, the tone has been wretched, culminating in the far-right anti-immigration riots sweeping through England and parts of Northern Ireland as I write. In this climate, why should anybody from a country with a long history of tension and trauma like South Africa have to contend with scrutinizing microaggressions from strangers? I have learned to spare myself from cringing comments like: We didn’t go to Johannesburg. We were too scared. There’s not much to see there anyway. But Cape Town is beautiful. It was like being in Europe. We had a fabulous apartment in Camps Bays, and saw no poverty or crime.

Still, however concise I am about my origins, it remains a contested issue, even a controversial one. In an increasingly essentialist world, many people and systems cannot comprehend the extraordinary levels of diversity communities like mine in South Africa contain. A good example is the drop-down ethnicity menu on official forms; the choices that best apply to me are usually absent, so that I always have to select: Other. If asked to elaborate, I say: African-South Asian. A few months ago, while in excruciating pain, an NHS administrator said she’d never encountered this ethnic mix, and it was not an option on her system. I suggested she add it because I was the evidence. She recommended we keep it simple and just say, “Mixed,” even though my precise ethnic makeup informed my diagnosis and treatment.

Another contention is identifying as Black, as I have always done, rejecting apartheid’s divide-and-rule classifications like Indian or coloured. As a student at the University of the Western Cape during the height of the anti-apartheid struggle in the late 1980s, I used Black to signify my anti-racist politicisation. However, there has been a shift in attitudes since then. In India, where complexion is an obsession and racism is rife, I was once offered consolation by someone who had completely missed the point: Why such a negative self-view? You’re not that dark. In the UK, several Global Majority Londoners have outrightly denied me this descriptor: You’re not Black, you’re brown. Once, I would have offered a rebuttal, but in these acrimonious times, things can turn hostile quickly. Today, race is not only vigilantly patrolled by the police. In South Africa, a friend from my community was recently accused of cultural appropriation for referring to themself as Black.

Yet, which of these contemporary race vigilantes still reads anything longer than a dodgy post? In a polarised world of rapidly expanding ideological dungeons, who still encounters, let alone tolerates, views from outside their own online echo chamber? In this context, it is becoming increasingly arduous to converse with ill-informed people who have strong views based almost entirely on suspect social media while being chronically under-read about everything else, resulting in them stomping through the world, hammers in hand, hunting for nails to hit on the head, scouting for hooks on which to hang their aggression. When these confrontations occur, I want to ask: Are you familiar with political blackness? It was an inclusive term used in the UK during the 1970s to describe everybody who could be a target of white supremacist racism. I want to recommend reading the Sri Lankan writer and former Director of the Institute of Race Relations, A Sivanandan. He said: Black is a political colour, not the colour of our skins. I want to recall the testimony anti-apartheid activist, Steve Biko, gave at South Africa’s 1976 Black Consciousness trial: Being black is not a matter of pigmentation—being black is a reflection of a mental attitude.

Today, the solidarity of such inclusive political blackness has been eroded whilst racist hard-right groups are on the rise, posting and reposting ignorance and lies in their determination to burn down the world. In the face of their ascendancy, how much safety can be found in designations like BAME? Writing about Fortress Europe in March 2006, I asked about the designation “ethnic minority”: And what comfort should the labelled take from a marker—ethnic—which in Europe also has a chilling history of association with a procedure—cleansing? Two decades later, with racism in the UK becoming more and more entrenched, my questions remain. How am I a minority when my combined ethnicities form the overwhelming majority of the population of this planet; simply because I live in England? Only in the UK, where the British government has a preferred house style for writing about ethnicity, am I given the demeaning label of “minority”. I refute it. Not even in apartheid South Africa, notorious for its dehumanising racial categorisation, was it used. In fact, the architects of apartheid avoided it to deflect attention from their own illegitimacy as a racist white minority government.

Besides, who imagines a violent right-wing rioter in a frenzy stopping to ask: I beg your pardon, but to help me decide the level of violence to inflict on you, are you BAME, or brown, or Asian, or mixed, so I can kick commensurate levels of shit out of you in accordance? Aren’t they more likely to just call you a “Paki” or a “towelhead” and kick all the shit out of you, regardless?

Strike through the façade and observe how insidious racial categories are designed to be squabbled over before ultimately being stamped for approval by a white establishment, ushered along by right-wing collaborators in conservative government think tanks. Such establishments have always masqueraded inclusivity by parading divisive figures like Kemi Badenoch to promote their actual agenda: maintaining class privilege and keeping whiteness supreme by projecting it as normative. For me, the only enduring way of resisting this pernicious system is to say: I am Black, and I write what I like.

*

My reticence about my origins also stems from knowing very little about them. My most sustained pursuit has been the acquisition of knowledge; being ignorant of my origins became a very heavy burden, a source of real anxiety. Disclosing my DNA findings has implications for those with whom I share biological ties. Out of consideration, I will not state ancestral names, differentiate between maternal and paternal lines, or reference contemporary familial ties. Ancestry was never fully discussed when I was growing up. Any questions I had were consistently averted or silenced, sometimes even with anger and force. Given my DNA results, I realise why I was muted. Elders may lie, but their epoch of suppression is over because DNA does not.

I was born in Johannesburg in 1968. My parents and grandparents were all born in different parts of South Africa, as, I had always assumed, were seven of my great-grandparents. So far as I know, only one of them was born outside South Africa, in India. This Indian ancestor is the one I know the most about, albeit very little. He migrated to South Africa during the second half of the nineteenth century. He started a family and a successful business, but died when my grandparent from him was just four years old. Apart from his names—misspelled by immigration officials in South Africa—marriage, offspring, property deeds, and death in 1922, nothing else I am aware of has been passed down about him or his origins in India. Nevertheless, while we were reared as South Africans first, there was a tacit understanding that we were South Africans of Indian descent. These were the boundaries placed on our genealogy. Exploring beyond them was not encouraged. Apart from India, no other nationalities were ever mentioned. However, for as long as I can recall, I always had the sense that something was being concealed.

A curious child, one to whom “No” meant a challenge to be explored later, when heads were turned. With a keen interest in history, I asked a lot of questions about my ancestry, especially with the onset of adolescence and early adulthood, but my elders weren’t forthcoming. Eventually, I recruited specialist genealogical researchers to trawl the National Archives And Records Service in Pretoria and the Cape Town Archives Repository for my seven remaining great-grandparents. Their search yielded nothing. That seemingly benign word—nothing—landed in my life with a thud, causing me to feel increasingly isolated and alone. No news is not always good news; even though my ancestral baggage contained very little information, it was metastasising into an increasingly heavy burden to lug around.

I am the first of my family to have returned to India since my great-grandfather left the subcontinent 160 years ago. I first went in 2004. Life in London was busy, with too many distractions for a young undisciplined writer. Offered the opportunity, I went to India to complete the manuscript I’d been working on for several years. My flight to Mumbai landed in the middle of the night. With several hours to spare before my connecting flight to Bangalore, I asked my friends to take me to the beach. Having set foot on Indian soil, I also wanted to touch the waters of the Arabian Sea, the kala pani or black waters that, in the wake of the abolition of slavery in 1833, had carried off more than 1.5 million Indians to toil as indentured labourers on sugar plantations around the British Empire.

We went to Juhu Beach. Upon touching the water, I cried, as I still do whenever I imagine their ordeal too much; they were doing the unthinkable. While India has the largest diaspora in the world today, at the time, leaving one’s homeland and crossing the sea was taboo, severing a sacred connection that would never be restored, inflicting a gaping wound that would never be healed. Eight months after that first night on Juhu Beach, while writing on my balcony in Bangalore, the title of my manuscript emerged: The Silent Minaret. I have travelled to India regularly since then, most recently from 2017-2019 to write my third novel, An Unwritten Life. For me, traversing the kala pani in my own time to produce these texts in India, has in some small way closed the circle, although it is buckled, restored the sacred connection, although the crack remains, applied balm to the gaping wound, although the scars are permanent.

And yet, these visits over two decades have never been primarily about my great-grandfather or establishing the specifics of my Indian heritage; because I know so little, there really is nowhere to start. Instead, I focused on contemporary India and my place in it during the early part of the twenty-first century, exploring my specific interests and location: the politics, cultures, religions, writing, cinema, music, fashion, Bangalore, genteel capital of the southern state of Karnataka, and, most importantly, the people and my relationships with the Indians who over the course of twenty years have taken me as their own and have become my chosen family there. Prioritising them does not mean I have forgotten about my great-grandfather, just that he remains as elusive and inaccessible to me as he has always been, even when I am in India itself. For years I assumed that he was an indentured labourer, so, upon my return to South Africa in 2019, I started searching for him in the Ships List of Indian indentured labourers to South Africa.

The list is extensive because indentured labourers were chattel of the British Empire about whom detailed records were kept, the most important being an indenture number, which took precedence over their name. Other information includes caste, port, date of departure, and the ship they sailed on. This was one of the most haunting pieces of research I have ever undertaken. For some indentured there are brief heartbreaking remarks, testifying to the harshness of the passage and the brutality of indenture: UNFIT TO WORK UNSOUND MIND / AGE 2 ORPHAN CHILD / WORKING AT HOSPITAL FOR FOOD / AGE 17 UNFIT TO WORK INSANE SINCE ARRIVAL / AGE 15 WITH 4 CHILDREN / AGE 20 WITH PHTHISIS / LEPROSY / DECEASED FEVER / DECEASED EXPOSURE / AGE 14 DECEASED ON BOARD / AGE 22 DECEASED ON BOARD CHOLERA / AGE 26 DECEASED ON BOARD DYSENTRY / AGE 16 DECEASED ON BOARD HEART DISEASE / AGE 26 SUICIDE / AGE 4 DROWNED / DIED SOON AFTER ARRIVAL / AGE 20 DEAD ON ARRIVAL.

Eventually, with the help of Mano Murugan of the Verulam Historical Society, I discovered that my great-grandfather was not on the list, meaning he could not have been an indentured labourer. Instead, he was a passenger Indian, merchants and business people who travelled independently at their own expense, like Mohandas Gandhi, who arrived in South Africa in 1893. Some further evidence I encountered in 2020 suggests that my great-grandfather, like Gandhi, might have been from the western coastal state of Gujarat. While this ties in with the broad profile of passenger Indians in South Africa, I cannot be certain. With this, I decided to lay my questions about my ancestry to rest. It had not been a lucrative quest. After decades of searching, I didn’t have much more to show than when I started.

Then, in January 2024, I received a serious medical diagnosis. Longstanding questions about my ancestry quickly resurfaced, so I submitted my DNA for analysis; I had to know the truth before it was too late. I thought it would clarify things. On the contrary, the truth is far more complex than I ever imagined. The first result was not surprising: South Asian, including India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. However, South Asia does not constitute the majority of my ethnic makeup. The immediate jolt was discovering that most of my genes are from other entirely unforeseen places. The ensuing blow followed quickly: the identity I was raised with was fake, negating everything I had been told about myself. I was devastated, not by the results, but by the deception. More truth, more pain; both will take a long time to process.

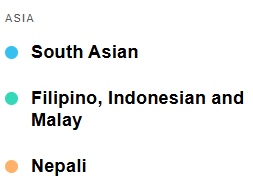

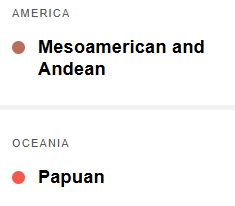

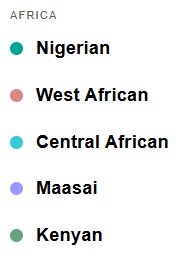

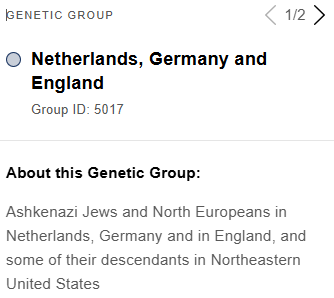

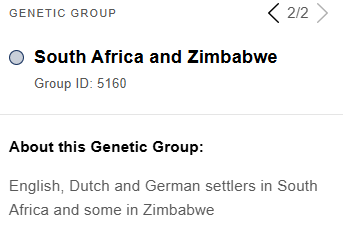

A few days after my deportation in 2015, I awoke from a nightmare, shouting: I was born nowhere. I was born somewhere. I was born everywhere. I immediately scribbled down these bizarre utterances. That was the start of An Unwritten Life. In view of my ancestry, that dream signalled a truth I was as yet unaware of. With two genetic groups and fifteen ethnicities, my DNA spans five continents: Asia, Europe, Africa, South America, and Oceania. Of great surprise are the regions to which most of my DNA has been traced: the Balkans, Eastern Europe, Britain, Mesoamerica and the Andes, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, West and Central Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Sudan, and southern Egypt; that policeman in Cairo was more perceptive than I realised at the time.

From Mexico in the west to the Solomon Islands in the east, I am truly the coolie on whom the sun never sets. One of the most extraordinary revelations is my Maasai DNA. While the extent of my ethnic diversity astonished me, I instinctively embraced it all, like love at first sight. I am not going to favour some ethnicities while relegating others as my elders did. That was their choice; it is not mine. Rather, I salute them all. Behind the fifteen coloured zones on my heritage map were real people. Together, they provide the answers I have been searching for my whole life. Cumulatively, all of them constitute me.

Premonitions sometimes presage affirmations. The pandemic prompted me to retrain in mental health, and I now work in suicide prevention. Part of the training focused on people from traumatic backgrounds in countries with a history of colonialism, famine, conflict, war, and genocide. We explored documentaries like David Harewood: Psychosis and Me, Fergal Keane: Living with PTSD , Jews, The Last Jews of Baghdad, 60 Days With The Gypsies and The Romanians Are Coming. In one of these programmes, the surname of a German Jewish family is mentioned, the same German surname as one of my grandparents. In another programme, the Roma hygiene codes of mokadi and mahrime reminded me of the cleanliness rituals I have inherited. My DNA results confirmed my growing suspicions.

After Asia, most of my DNA is not African as I had supposed, but European, particularly Balkan, as indicated by the pink area in southeastern Europe on my map. It includes Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Sebia, Croatia, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. On the surface, it may seem baffling that my ancestors were Balkan, until one takes the long view of human migration. The Balkans has sizeable Roma populations, and the Roma originated in northern India, the name evolving from the original Sanskrit, doma, the “untouchable” Dalit caste. The Romani language, Romanes, is an Indo-Aryan language, and the sixteen-spoked red chakra wheel on the Roma flag denotes our Indian origins. It is to this population of Balkan Roma that my South Asian DNA has been linked.

Often referred to as Europe’s forgotten people, the Roma are one of Europe’s most marginalised groups. But forgotten and marginalised by whom? Structural discrimination against the Roma is relatively well documented, their expurgation from South African family trees like my own far less so. Overlapping with the Balkans and intersecting with Romania, Bulgaria and Bosnia and Herzegovina is a larger yellow area in Eastern Europe, which includes Ukraine, Austria, Czech Republic, Poland, Belarus, Russia, and Germany. This region represents the most astonishing revelation of my heritage: my Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.

Ashkenazi Jews are part of the European Jewish diaspora, originating in Germany and France, with later migrations to Poland and the Slavic states. When I learned that Ashkenaz is the Hebrew word for Germany, I immediately remembered my grandparent’s German surname, and how my questions about it were always stifled. Of the almost nine million Jews who lived in Europe before World War II, most were Ashkenazi, six million of whom were exterminated along with an estimated 250,000–500,000 Roma during the Holocaust. Many Ashkenazim who survived the war emigrated to countries like the USA, Canada, Australia, and South Africa. In fact, South Africa is home to the twelfth largest Jewish population in the world, and the largest population of Jews in Africa, where most Jews live in the city of my birth, Johannesburg.

What is one to do when realising that most of one’s lineage was expunged and supplanted with a deception? How does one reestablish a sense of self after it has been obliterated? I’ll do what I have always done in my attempt to understand complexity: write. While the road ahead is long, South Africa is no longer a repressive state, but a constitutional democracy, its “born free” generation comprising 40% of the population. Not having been born free, I constantly have to strive towards becoming free. Towards this end, I am breaking with past repressions by sharing the DNA knowledge I have acquired. I will not leave behind a filtered legacy of elision like the one I inherited. Interpreting my DNA through the lens of apartheid, I am grappling with new dimensions of suppression, not just at the public level of the state, but also privately, inside families, illustrating in the most unanticipated way Nadine Gordimer’s famous quote : “Censorship is never over for those who experienced it. It is a brand on the imagination that affects the individual who has suffered it, forever.” My elders are now deceased, so I will never be able to discuss my DNA with them. Instead, I have to confront the jettisoning of certain ethnicities from my lineage over time. Never to know their reasons, I attempt reconciliation by acknowledging that apartheid legislation imposed cruel choices. However, haunting questions linger: How much of my diversity was forced, born out of exploitation, compulsion, coercion, abduction, enslavement, forced marriage, or rape? Was the truth simply too painful to disclose?

I am left with new insights into just how heinous apartheid was, and a growing awareness of how enduring its effects will be. Apartheid is the curse that keeps taking, leaving in its wake a trail of loss that can never be recovered, not just of assets, but of access to people, communities, ancestry, entire lineages, and all their legacies. Faced with the new knowledge of my prodigious ethnic diversity, I lament how apartheid dynamics bulldozed this rich mosaic, eroding its complexity to the point of complete obliteration from the record. Such erasure resulted from concerted efforts over generations to conceal the hybrid consequences of South Africa’s unique geographical location; the only country in Africa and one of the few in the world to be bounded by three oceans, it has funnelled the global gene pool for centuries, rendering the fallacy of “racial purity” obscene.

Given the sweeping breadth of our history, I cannot be the only South African from such a diverse gene pool. Increased DNA testing by more South Africans in the future will demonstrate this, amplifying our grasp of the past and of who we are as a nation. While I understand the pressure brought by repressive legislation to comply, I feel an enormous sense of loss at the enduring effects thirty years after the end of apartheid. I am angry that, despite several opportunities for truth and reconciliation since the end of apartheid, my elders never found the courage to speak to me as an adult about the questions I constantly raised as a child. Instead of truth, they favoured deception. If you deceive a child, you send a crack through the universe that splinters through time and into the future.

The history of Europe, the Holocaust, the Roma Holocaust, and the resurgence of hard-right extremism, especially in the Balkans, elicits even greater sorrow and concern. Before my DNA revelations, I empathised with the victims and survivors of the Holocausts as fellow human beings. Now, my DNA has personalised the Holocausts in a way I never foresaw. They were not just historical figures in one of the greatest calamities in contemporary history; however distant, forgotten, and redacted from my genealogy, they were ancestors. And how vulnerable am I to feel about my Ashkenazi Jewish heritage? In 2023, hackers advertised the data of people with Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry on the dark web, raising fears about targeted attacks. I have come to see how, as in nature, there are no straight lines of separation in history; everything is intertwined and cyclical. Given the current state of the world, I fear that such conflagrations are on the horizon once more. I pray I am wrong. If not, who will be expunged in the genocides to come?

My views on the Occupied Palestinian Territories have been clear from the start. They run through all my writing, and my discoveries do not change them; Palestinians deserve recognition and justice, just like everybody else. Scheduled to attend legal proceedings instituted by South Africa against Israel at the International Court of Justice in The Hague on 11 January 2024, I was instead hospitalised the night before boarding the Eurostar from London. It was a narrow escape. According to my physicians, had I been taken ill on that train the following morning, I would not have survived the journey.

Seven months later, writing against the backdrop of ongoing genocide in Gaza and far-right riots in the UK, I am grateful to modern science for restoring my forgotten past. As I survey the fifteen coloured regions of my heritage map, to my ancestors from there, I say: All Hail. I feel honoured to be the custodian of the phenomenal ethnic diversity they have bequeathed me. In an increasingly fractured and sectarian world, I am writing this to bear witness to that diversity, and to make it count. Mine is not just a solitary family tree, but an entire unexplored jungle. From north to south, east to west, whole worlds live on in me. I wager that if everybody took a DNA test, there’d be fewer riots and wars, mitigating our prejudice and xenophobia as we realise more fully just how closely interconnected, we truly are.

*

I rise at four, and am at my desk when the first planes start arriving from their overnight flights at around five-thirty, circling in their holding patterns over London before landing at Heathrow. After the faint dawn chorus, it is the most glorious sound of the day, all those migrants on their own grand voyages, a time when I start humming Jimmy Cliff’s anthem to migration, Many Rivers To Cross. This is my tribute to them because why should voyages of discovery be the sole preserve of colonising dead white men?

When Britain faced its darkest hour, we were the redacted “Empire beyond the seas,” which wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill called to save this island from impending subjugation, and we did, while the USA dithered. I say “redacted” because this last part of Churchill’s famous speech is frequently omitted from filtered versions of history, which is why I am resurrecting it here, along with my ancestors who fought and died in defence of these islands. Now, we will travel to them on the seas and oceans and through the air. We will arrive on the beaches and the landing grounds, in the fields and the streets and the hills. We will never stop coming. Never stop in our struggle for a new world to liberate the old.

In 2015, I wrote: “To journey is to be human. To migrate is to be human. Human migration forged the world. Human migration will forge the future.” At the time, I had no notion of the extent to which global patterns of human migration had in fact forged me. My ancestors were not locally confined people, but global migrants of truly epic proportions. In 2021, I described mine as having been “a nomadic life, a life of incurable wanderlust, a life lived on the move.” I have always wondered where the impulse arose, the urge to look at the horizon and ask: I wonder what’s over there? Now, I have the answer: blame me on my ancestors. In whatever time remains, I intend to pay homage to them by continuing my grand voyage, visiting the new countries on my heritage map. I’ll take along my map, and should anybody in my ancestral countries ask: Where are you originally from? I’ll show them my map and answer: I’m from here.

Ishtiyaq Shukri

London

13 August 2024

In memory of Anne Harte: Lagos 1961 – London 2024

Related:

249th Appleby Horse Fair, 5-11 June 2025

Resistance Leaflet | Elon Musk: Burning self, not gasoline

In 2016, I left Twitter during the electoral campaign of the 45th president of the United States. For me, the tone on the platform had become unbearable. Even though I did not follow the president-elect, relentless media coverage forced his terrifying view of the world into my newsfeed. Unable to circumvent this, I left the site.

The relief was instant, and Twitter quickly became irrelevant in my life. Aware of your takeover of the platform in 2022, I paid very little attention. Also aware of your rebranding of the platform to X in 2023, and the escalating reports of toxicity on the site since then, I felt disconnected from those issues, and somewhat vindicated for having left six years earlier. I resolved to just steer clear of you and your malign influence. Those were errors of judgment. Thinking that we are immune to global issues and people like you is a dangerous mistake. When I woke up, you had swerved right into my lane.

You have been described as “controversial,” your posts on X as “erratic,” and “bizarre,” adjectives that play into the image of the whacky-but-harmless scientist. None are accurate. Simply put, you are dangerous. There is nothing erratic about you. On the contrary, you know exactly what you are doing.

In the summer of 2024, during the worst riots the UK had seen in decades, you used X to further fuel discontent, posting that "civil war is inevitable", and re-posting faked images that had been shared by Ashlea Simon of the far-right Britain First party announcing “emergency detainment camps” on the Falkland Islands for rioters. Since then, you have relentlessly trolled the UK in appalling and terrifying ways. By stirring the issue of grooming gangs, you have shown little regard for the survivors. Rather, there have been renewed calls for ethnic profiling from right-wing politicians. The poll you conducted on X about whether “America should liberate the people of Britain from their tyrannical government” received a majority: of the 1,998,221 votes cast, 58% voted in favour, with an additional 94.4K likes. This is chilling. What did you hope to achieve? Given the militancy of your constituency, “liberate” could incite a range of violent actions, and you know it. While feelings of invincibility live in the present, consequences reside in the future. On 20 November 2024, you were invited to a UK parliamentary inquiry into the role of X in escalating the 2024 riots. The inquiry is pending. On 10 January 2025, the UK announced that officials in Homeland Security are monitoring your social media posts.

Most chilling, is your endorsement of the right-wing AfD party in Germany ahead of federal elections there on 23 February 2025, when the 20th century’s history of right-wing politics in Germany is known, with two wars that engulfed the world. Again, you know this. My question is: How sincere was your visit to Auschwitz death camp in January 2024 after X was criticised for antisemitic posts and you for promoting antisemitic conspiracy theories?

When recalling the horrors of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany, a common question is: How could such things have happened? The answers are plain. They happened because people like me said nothing, and did nothing. We looked the other way, or dug our heads in the sand, as I did, trying to avoid and to steer clear of you instead. They happened because people like me were uncritical of an extensive Nazi propaganda campaign of cartoons, posters and films led by Nazi Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels.

Not wanting to repeat those catastrophic mistakes, I sat down to write to you directly. By examining you more closely through writing, I have come to realise that you are in fact bringing about your own demise. As history has demonstrated time and again, nobody survives the fascist allegiances you are forging now. Even as you appear to be on the rise, your fall has already been written, and is now inevitable, just a matter of time. With growing calls to boycott your products, and the ascent of rival EV manufacturers, Tesla profits have fallen sharply. You have been as reckless with the reputation of your brands as you have been in your political interference in other countries. We will not tolerate it.

What remains of your credibility when AI-generated images associating you with Nazism already abound? Why would affluent Londoners want to be seen in a Tesla when there are AI images of Hitler driving one? Wait for the tipping point, then watch them dump the brand. I certainly don’t wish to be seen in one. When I order a taxi, I immediately switch the ride the moment I realise that a Tesla has been dispatched.

The truth is, I have known men like you all my life: privileged, entitled, narcissistic, racist, bigoted and abusive bullies. In fact, you have something in common with one of them, Roy Snyman, the Anglican priest who sexually abused me from the age of ten: you both attended Pretoria Boys High, South Africa, which raises another topic on which I must insist. We have mutual ties with Pretoria and South Africa, but I cannot overstate the extent to which I am distancing myself from you. I have seen what men like you can do. I have felt what men like you can do. You terrify me, absolutely. You must be resisted. The alternatives are horrifying. Human beings are inclined towards making the same mistakes, and history towards repeating itself. I desperately hope that we won’t let it come to that.

Ishtiyaq Shukri

London

15 January 2025

Related:

UK group projects ‘Heil Tesla’ and Elon Musk’s hand gesture onto German factory | The Standard

Elon Musk’s Tesla showroom defaced with swastikas in the Netherlands – POLITICO

Musk politics? Tesla sales slump in UK, European markets | Reuters

Musk says EU 'should be abolished' after fine against X

The billionaire white South African fascists in the palm of your hand

To the President of South Africa, the Prime Minister the United Kingdom, my local London Labour Member of Parliament, my publishers, vice chancellors and academics in English and African literature departments in my almae matres, Shukri scholars and research students, the Goethe Institut and other cultural and literary organisations, associates, colleagues, family and friends.

If you are still under the illusion that 1994 was a miracle year that made white South African racism, economic exploitation, gender apartheid and right-wing extremism unacceptable, focus your attention on the three billionaire tech bros surrounding US President-elect, Donald Trump: Elon Musk, Peter Thiel and David Sacks. Also known as the PayPal Mafia, they are the right-wing white South African misogynists about to take over the White House. In his farewell address delivered on 15 January 2025, outgoing President Joe Biden warned about “a dangerous concentration of power in the hands of a very few ultrawealthy people, and the dangerous consequences if their abuse of power is left unchecked. Today, an oligarchy is taking shape in America of extreme wealth, power and influence that literally threatens our entire democracy, our basic rights and freedoms and a fair shot for everyone to get ahead. We see the consequences all across America.” The only African immigrants in Trump’s administration, these three men epitomise Biden’s warning. While much has been written about them individually in relation to tech and Trump, their links to apartheid South Africa warrant longer, more specific scrutiny. Whether you stay or whether you leave, no South African is untouched by the country’s racist history. Apartheid continues to be South Africa’s greatest influencer. Now, it’s about to become America’s, too. Step aside, KKK. It took three billionaire South African racists less than 30 years to achieve what you could not in 160—control of the White House. And they’re not stopping there.

German federal elections are scheduled for 23 February 2025. One of the leading candidates in the race is the far-right politician, Alice Weidel, representing Germany’s second-largest opposition party, the Alternative for Germany (AfD). To the AfD, the horrors of Nazi Germany are a “cult of guilt.” That is shocking, but not surprising; Weidel’s grandfather was Hans Weidel, a Nazi judge directly appointed by Adolf Hitler. This would concern most, but not the close advisor to Trump, Elon Musk. Despite his visit to Auschwitz death camp in January 2024, he has endorsed the AfD as Germany’s “last spark of hope.” Plot points of the sequence of events leading up to this endorsement are important.

In 2024, a study conducted at Queensland University of Technology into potential algorithmic bias on Musk’s social media platform, X, suggested that Musk may have tweaked the platform’s algorithms to artificially amplify his posts. On 9 June 2024, a 24-year-old German influencer, Naomi Seibt, posted on X that she had voted for the AfD. That post received 830.9K views. On 19 December 2024, Seibt posted that the leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), Friedrich Merz, “staunchly rejects a pro-freedom approach and refuses any discussion with the AfD.” That post received 36.5M views. The following day, on 20 December 2024, Musk responded to Seibt’s post. True to form, Musk’s post was brief: “Only the AfD can save Germany”. It received 52M views. On 10 January 2025, Musk went even further, hosting a 74-minute live chat with Weidel on X. Opinion polls suggest an AfD surge, with the party currently holding a vote share of 21%. It is worth remembering these dates. They mark the beginning of a new world order, the confluence of ultra wealth, borderless high-tech influence, and fascism. It is also worth recalling the Nazi’s rapid four-year progress to election victory: in 1928, they held 12% of the vote. That increased to 18% in 1930, and 38% in the German federal election of 1932, making them the largest party in the Reichstag.

Musk was born in South Africa’s administrative capital, Pretoria, in 1971. His abusive father, Errol Musk, was a one time member of the Progressive Federal Party and supporter of the divisive Tricameral Parliament, a three-tiered racially defined parliamentary system, which excluded black South Africans. But “progressive” at the height of apartheid was a relative term. He also traded emeralds from a mine in one of the world’s most emerald-rich countries, Zambia. Telling is his continued use of the old colonial name “Rhodesia” as he narrates the story; the country officially became Zimbabwe in 1980. In his authorised biography, Elon Musk, Walter Isaacson quotes a line from an email Errol sent to Elon. It captures the enduring culture precisely: “With no whites here, the blacks will go back to the trees.” The email was written in 2022.

Tech billionaire, Peter Thiel, an early investor in Facebook and cofounder of PayPal, Palantir and Founders Fund, was born in West Germany in 1967. In 1968, the family emigrated to the USA. Then, during the height of apartheid in the 1970s, they moved to South Africa and its neighbouring former German colony, South West Africa, now Namibia. What could possibly have been their motive? Namibia is a country with one of the largest uranium deposits in the world. At the time, it was under South African control, and Thiel’s father, Klaus Thiel, was involved in the extraction of uranium for use in South Africa’s apartheid-era nuclear development programme. This is the context of Thiel’s childhood and early education in whites only schools. In his biography of Thiel, The Contrarian, Max Chafkin references conversations at Stanford University in which Thiel is reported to have said that apartheid “works” and is “economically sound.” According to Chafkin, Thiel’s economic and political philosophy borders on fascism. “He is hostile to the idea of democracy.” On 10 January 2025, the Financial Times inexplicably published an incoherent opinion piece by Thiel. Like his essay, The Straussian Moment, it is characterised by pompous, incomprehensible pseudo-intellectual posturing, providing an informative glimpse into the workings of a delusional mind. Referencing pre-revolutionary France, Jeffrey Epstein, John F Kennedy, Anthony Fauci and Covid-19, Thiel’s central premise is that: “Trump’s return to the White House augurs the apokálypsis of the ancien regime’s secrets. The new administration’s revelations need not justify vengeance—reconstruction can go hand in hand with reconciliation. But for reconciliation to take place, there must first be truth.” I specifically reference this piece because Thiel’s chosen title is telling: A time for truth and reconciliation. By conflating Trump’s second term with South Africa’s post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Thiel demonstrates a catastrophic misunderstanding of both.

Tech venture capitalist, David Sacks, the former Chief Operating Officer of PayPal, is Trump’s appointment as White House A.I. & Crypto Czar. Born in Cape Town in 1972, the family emigrated to the US when he was five. In 1996, while they were students at Stanford, Sacks and Thiel co-authored The Case Against Affirmative Action and The Diversity Myth: Multiculturalism and Political Intolerance on Campus. The book argued that politically correct multiculturalism on campuses was debilitating. In it, Sacks and Thiel also offer their views on date rape: “seductions that are later regretted.” In 2016, Thiel apologised for the comments on sexual assault contained in the book, but I question his sincerity. A telling sign of his hubris is the title of his June 2023 address at The New Criterion event honouring him for services to culture and society, The diversity myth: On multiculturalism and misdirection. In his speech, he insists: I still think that almost every point we made was right. There’s very little that’s wrong. He repeated the address at the Roger Scruton Memorial Lectures in October 2023.

Like cliquish immigrants, Musk, Thiel and Sacks have orbited one another their whole careers, apartheid South Africa their common origin story. They embody a new time, the collision of past, present and future. With them, the future has kicked down the front door, while the past is breaking in through the back. Now we're mediating all three cantankerous eras at once, like feuding family members under the same roof. What do you imagine these men are going to do in the White House? Be naïve, but at your own expense. From past behaviour, we can predict future action. See their ravenous quests for more, insatiable appetites only satiated with superlatives. 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is not a final destination for them, but a stepping stone, a propeller to their dystopian view of the world. We once speculated that they might use tech to build a better world. Clearly not. They simply used it to reinvent and escalate the world of their fathers, a heartbreaking contemporary illustration of that timeless line from Seven Pillars of Wisdom by TE Lawrence: “Yet when we achieved, and the new world dawned, the old men came out again and took our victory to remake it in the likeness of the former world they knew.”

Wherever you are in the world, you would be mistaken to see these three horsemen of dystopia as distant and removed. They’re a lot closer than you might think. In fact, they’re already in your healthcare, in your driveway, in your house, on your desk, in the palm of your hand. Question: What are you going to do about it? Think carefully, dig deeply, because red poppies come November won’t suffice.

Whatever the tech bros say, truth will always prevail, no matter how long it takes. Facts matter. So does fiction. Given the context, one novel stands out: Philip Roth’s, The Plot Against America. I first read it in a Palestinian refugee camp during a long stay in the West Bank from 2006 to 2007. At the Israeli controlled border crossing from Jordan into the occupied West Bank, soldiers searching my luggage repeatedly set aside the novel, and instead quizzed me about the battery in my laptop, my charger, the refills for my fountain pen, holding each up in turn and asking: What’s this? I thought they were joking. They were not. Nobody asked about the book.

In the speculative novel, Roth writes an alternative history in which a Nazi sympathiser, Charles Lindbergh, defeats Franklin D Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election, leading the USA to become an ally of Nazi Germany. This is why I read fiction; why I write it. Fiction is the finest form of fact. One of the most famous quotes from the novel anticipates the advent of the unforeseen: “Anything can happen to anyone, but it usually doesn’t. Except when it does.” Now the unforeseen has come to pass, and we’re all terrified. Maybe now we can talk about the book, before it really is too late.

Ishtiyaq Shukri

London

18 January 2025

Related:

South African president phones influential billionaire Musk after Trump's funding threat | AP News

US top diplomat Rubio will not attend G20 meeting in South Africa | Reuters

Government of South Africa notes the USA Executive Order